Saturday, 28 October 2017

02:36 PM

Here's a keen thing I learned about from a Vox article: a Chrome extension named Library Extension that adds library information when you're viewing books on Amazon or Goodreads. The extension tells you whether the book you're interested in is available in one or more library systems.

Let's say you're interested in the book The ABC of How We Learn, so you look it up on Amazon. In the bar at the top of the page, the library extension icon lights up to tell you that you're on an enabled site:

On the actual page where you're viewing book information, the extension displays library information:

If you want to get the book from the library, you click the Borrow button. This sends you to the library site with the book preloaded.

To configure the extension—for example, to tell it which libraries you want to look in—you click the icon in the toolbar, then click Options:

In the options dialog, you find the library you're interested in, then click the add (+) button:

I just started using this, so I don't know whether I'll end up liking it. It seems a bit intrusive to actually inject information into the page, instead of optionally displaying that information in a dialog or something. I also don't know how robust it is. Does the extension rely on Amazon APIs? Does it scrape information from the page? (A strategy known to be fragile.) How reliable will it be in terms of interacting with library sites?

But I like the concept just fine, since it reflects something I do a lot anyway—namely, look up books, then see if I can get them at the library. I'm curious whether others use this extension, or something like it, and what they think.

[categories]

books, readings, technology

|

link

|

Friday, 30 March 2012

07:05 PM

More Friday Fun. This week I celebrated 15 years as a full-timer at Microsoft. My colleagues at work took me out to lunch and presented me not just with the giganto crystal that you get from the company as your 15-year marker, but with a very cool present: a book. Not just any book, tho — it is, to quote the title page in full:

The Scientific and Literary Treasury: A New and Popular Encyclopedia of The Belles Lettres: Condensed in form, familiar in style, & copious in information;

Embracing an extensive range of subjects in Literature, Science, and Art. The whole surrounded with Marginal Notes, containing concise Facts

with appropriate observations. By Samuel Maunder This was published in 1858 in London. (Actually, it’s the revised edition — the original was published in 1840.) It’s a beautiful little (literally little) book, bound in leather with an embossed title on the spine. Here’s a picture:

(The glasses are in fact required; the book is set in 6-point type.)

And here’s a picture of the title and faceplate.

The evening after the lunch, we were piled on the bed while Sarah read selections to us out of the treasury. There is of course a certain style to books written in the mid-19th century, but Mr Maunder also has a distinct personality. Here he is in the Preface, introducing his work:

There are few tasks of more difficult accomplishment, than the one which an Author feels bound to undertake, when a performance which has engrossed much of his time, and to which he has probably directed his best energies, is about to be submitted to the public. Literary usuage appears, however, to have decided, that upon such an occasion, some prefatory observations are considered indispensable ; but, while prompted by a natural desire to enter somewhat freely into the merits of that which has occupied his most earnest attention, the overwhelming apprehension of being thought egotistical, and the bare possibility of really becoming so, will often paralyze the Writer’s well-intention efforts. In the present instance, I can truly say, that my incessant occupation from the hour I commenced this volume to the very eve of its publication, coupled as it has been with an anxious desire to render it worthy of public favor, have left me no time to consider what arguments would most likely to fix the reader’s attention to the following pages ; in what terms I should entreat his kind indulgence ; or upon what grounds I could venture to deprecate the severity of criticism.

May I be allowed to say, that I have endeavoured to produce a work, which — while I am fully sensible of its numerous imperfections — I trust, may be generally acceptable, and, I hope, extensively useful? I was also delighted with the following passage from the Preface, which in my line of work is known as “setting audience expectations”:

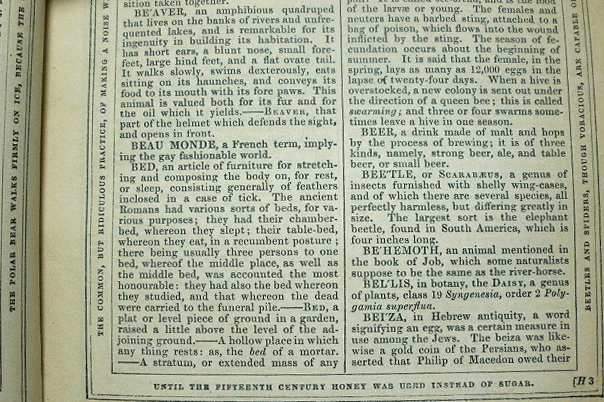

I am well aware how natural it is for a person who is engaged in any particular study, or who has a predilection for some given topic, to be desirous of making himself as fully acquainted with it as possible, and to feel, perhaps, a degree of disappointment, where another person, with different views and pursuits, would be abundantly satisfied ; but the candid reader, I am persuaded, will grant, that a complete system of any science can hardly be expected in a work whose highest excellence must, after all, be a judicious brevity ; and that if the principles be clearly stated, they will often suffice till the details can be sought in works especially adapted for their elucidation. My great object has been to produce a book that should meet the wants and wishes of a very large and most respectable class of readers, whose opportunities of studying the ponderous tomes of science are as unfrequent as their aspirations after knowledge are ardent. To the literati, I know it can present few attractions ; to the man of science it presumes not to offer anything new. But there may be times, when even these may find it convenient to consult a hand-book of reference, so portable and yet so full, if it be merely to refresh the memory on some neglected or forgotten theme. As promised, the book has marginal notes on every page containing concise Facts. Here’s a picture of one page that shows that there’s a Fact not just on the bottom, but running up the page:

We decided that Our Author had certain predilections himself. For example, consider the contrast between the entry for Dog, which begins like this and goes on for about the same length again:

DOG, (Canis familiaris), an animal well known for his attachment to mankind, his incorruptible fidelity, and his inexhaustible diligence, ardour, and affection. But when we thus describe this faithful animal, we mean those only which man has domesticated. In his wild state the dog is a beast of prey, and of the wolf kind, clearing the earth of carrion, and living in friendship with the vulture. By Mahometans and Hindoos the dog is regarded as impure, and neither will touch one without an ablution ; they are therefore unappropriated, and prowl about the towns and villages, devouring the offal, and thus performing the office of scavengers. Tamed and educated by man, the numerous good qualities of dogs have claimed and received the tribute of universal praise. Their sensibility is extreme ; witness their susceptibility of the slightest rebuke, and restless anxiety to be restored to favour. Uninfluenced by changes of time and place, these animals seem to remember only the benefits they may have received, and, instead of showing resentment, will lick the hand from which they have received the severest chastisement. The skill of several species in the chase, where they act as the purveyors of man ; their domestic habits ; their kindness to children ; in a word, their general congeniality with man himself, have, in all ages, recommended them to his use and care.[…]

… and the entry for Cat; this is it in its entirety:

CAT, a well known domestic animal, of the feline genus, but sometimes wild in the woods, and large and ferocious. Anyway, we’ve been having a great time with this book, and all agreed that Mr Samuel Maunder must have been an interesting and congenial person himself. (His apparent aversion to cats notwithstanding.)

[categories]

FridayFun, books, personal

|

link

|

Wednesday, 30 September 2009

08:50 AM

The stererotype of the librarian is often as either meek or as a stern shusher of patrons who just wanna have fun. (Marian the Librarian) As for meek, I was early exposed to the elderly Mrs. Clark, who deftly maneuvered an eight-ton bookmobile around Aurora, CO, and who moreover could handle hordes of excited elementary students. No meek there. And as for the shushing, whether that ever was true, my latter-day experiences at the library, where they have vending machines (!!!), have long since corrected any such misunderstandings on my part.

A stereotype that might not often be associated with librarians is that of radical. And yet as a group, they most certainly are. Specifically, librarians as a group are radical about our right to read anything. As evidence for this, every year at this time we observe Banned Books Week, sponsored by (among others) the American Library Association.

When you think about it, libraries really are astonishing. Their charter is to open the world of information to anyone who wants it. Any information, free. In my experience, librarians take this charter very seriously. Read the preface of any non-fiction book, and odds are good that you will find an author's grateful acknowledgment of the tireless assistance provided by a librarian, whether it's at the Library of Congress or the town library in some hamlet. (These days, of course, being off the (physical) beaten track is no barrier to finding information through your library.)

The charter of libraries and librarians is to help patrons find information, not to judge whether the information is good or bad, useful or not, or -- here's the point where things get sticky -- harmful or not. You and I might disagree about whether we think a particular book, say, is good, or useful, or a pox on society. Libraries do not make that decision for us, nor do they, as much as possible, allow others to dictate these things.

Thus Banned Books Week, which reminds us that over the years, books such as The Great Gatsby, Beloved, Invisible Man, Gone with the Wind, Slaughterhouse-Five, The Jungle, A Clockwork Orange, and The Satatnic Verses have all been challenged or banned.

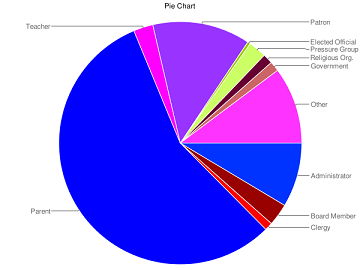

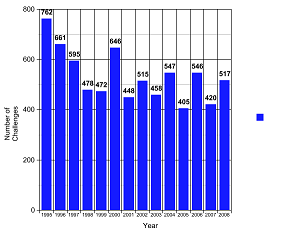

As part of Banned Books Week, the ALA posts information on its Web site about banned and challenged books. For example, if you're interested in why the books were challenged, there's a page that lists specifics for individual books. A page I found particularly interesting shows a set of charts that summarize who and when and why books have been challenged over time.

Last year, the librarian Jamie Larue blogged the story of a challenge to a book named Uncle Bobby's Wedding, which is a children's book about gay marriage. Surely the topic of gay marriage is not appropriate for a children's book, right? I urge you to read the blog entry, the comments, and the spillover into other blogs.

We cannot take for granted our unfettered access to information. The ALA doesn't, which is why they set aside a week to remind us that it is a never-ending discussion to determine who may read what, and that the library is in the middle of it all. As they quote on their site: If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.

--Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan

[categories]

books

|

link

|

Thursday, 24 September 2009

10:46 AM

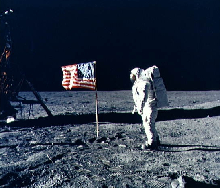

As we know, I like reading about the history of technology, and as we also might know, I am a fan of aviation. One of my favorite books is Tom Wolfe's The Right Stuff, which is a history of the Mercury space program.

Recently I've been reading Rocket Men by Craig Nelson. This is a history of the Apollo 11 moon shot, with side trips into the history of rocketry, the Cold War, and related topics. Where The Right Stuff is a kind of cultural history (of test pilots and of the unexpected sainthood of the Original Seven), Rocket Men is more about the engineering that went into the Apollo program. Although it is for a general audience, it goes into quite a bit of (interesting-to-me) technical detail about the Apollo program and the moon mission in particular. Recently I've been reading Rocket Men by Craig Nelson. This is a history of the Apollo 11 moon shot, with side trips into the history of rocketry, the Cold War, and related topics. Where The Right Stuff is a kind of cultural history (of test pilots and of the unexpected sainthood of the Original Seven), Rocket Men is more about the engineering that went into the Apollo program. Although it is for a general audience, it goes into quite a bit of (interesting-to-me) technical detail about the Apollo program and the moon mission in particular.

For those inclined in that direction, there are many astounding facts and stories. A small example: when the LEM and the CM decoupled in preparation for the LEM descending to the moon, the airlock between them was not 100% evacuated. As a consequence, when the LEM disengaged, it was accelerated by the small remaining air pressure (a small puff of air, basically) and ended up going 20 feet/second faster than planned. The ultimate result was that they couldn't land where they had planned, and Armstrong basically had to hunt around for a suitable landing spot. He put down with virtually no fuel to spare.

Ok, so, as I like to do, I copied out a few of the cites that I was marking as I read. If you're with me so far, maybe you'll find these interesting also. Cites are slightly edited for length.Before the 1990s' Silicon Valley entrepreneurs with their Red Bulls, boxed pizza, and Cheetos, there were the short-sleeved-white-shirted denizens of Houston's NASA with pocket protectors, Mexican takeout, evaporating hot-plate coffee, and ashtrays choked with smoldering cigarette butts, and before them were New York and New Mexico's Manhattan Project brain trust of alpha engineers in their fedoras and soft, floppy jackets.

In so many ways, the race to the Moon would turn out to be a sequel to its predecessor's race for atomic mastery. Both were enormous projects that only a great nation, on a federal level, could afford to attempt, and achieve. Both began with Third Reich émigrés, and a shared geography. [i.e., New Mexico--ed.] And, if the first lunar landing marked the end of the Space Race and one of the beginnings of the end of the Cold War, the Manhattan Project marked both the end of World War II and the Cold War's birth. Nelson thinks that NASA and the space program get short shrift in our current thinking about our capabilities as a nation:Why is it so difficult to honor the engineering greatness of NASA? It should be seen as part of a string of American accomplishments reaching from the inventions of Bell, Carver, Morse, and Edison, to the triumphs of the Erie Canal, the St. Lawrence Seaway, the Transcontinental Railway System, the Rural Electrification Administration, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Hoover Dam, telecommunications satellites, the Internet, and the Global Positioning System. Such dazzling achievements, whose dynamism is a key force in American identity, are today more often than not undervalued, or just ignored by civilians. Our civilization (especially the continent-wide, U.S. variety) could not exist without the big pipes, the vast roads, the power grids, the dams, and the people-and-cargo-carrying vehicles of heroic engineering and big science. This story makes me laugh every time:The storyline [of Wernher von Braun's life] was eventually developed by Columbia Pictures into a 1960 biopic, I Aim at the Stars, which in turn inspired a famous line by the Kennedy speechwriter Mort Sahl, who quipped that during World War II, von Braun "aimed at the stars, but often hit London." Something we don't normally think about ... Nelson notes that the Command Module had about as much room as the front seat of a car.If astronauts and cosmonauts are considered particularly brave, it is not just because they were the first to travel into outer space, but also because they willingly endured what could only be described as the world’s worst camping trip—perhaps the reason why so many NASA moonwalkers were onetime Boy Scouts. To begin with, while space food technology was considered thrillingly modern in 1969, that was a view held only by those who didn’t have to eat it. ... which was followed by an unappetizing description of the mush that they ate, and then how certain ... other ... functions were accomplished. I think it was Aldrin who observed that the bravest man in the space program was the Navy frogman who had to open the hatch of the recovered capsule after three guys had been shoehorned into it for a week.

I found the following oddly chilling, trying to imagine what it might have felt like if, as was absolutely possible, Armstrong and Aldrin had been stranded on the moon[1]: Armstrong dropped from the rung to the Eagle's footpad, and then jerked himself back onto the ladder, to make sure that after their EVA [extra-vehicular activity], he and Aldrin would be able to climb back aboard their ship. He then warned Aldrin about what "a long one ... a three-footer" the small step actually was. Aldrin, meanwhile, had to remember not to lock the cabin door after exiting Eagle, since the designers had neglected including a handle on the outside. Armstrong dropped from the rung to the Eagle's footpad, and then jerked himself back onto the ladder, to make sure that after their EVA [extra-vehicular activity], he and Aldrin would be able to climb back aboard their ship. He then warned Aldrin about what "a long one ... a three-footer" the small step actually was. Aldrin, meanwhile, had to remember not to lock the cabin door after exiting Eagle, since the designers had neglected including a handle on the outside.

Armstrong was practically a caricature of the laconic (if not tongue-tied) pilot-hero. He was remote even by the standards of his profession. But in addition to his famous quote ("small step for [a] man ..."), he occasionally did have some observations, even if they were a little odd:Armstrong: "The horizon seems quite close to you because the curvature is so much more pronounced than here on earth. It’s an interesting place to be. I recommend it." As I say, the book is a more technical peek at the space program, and at 350 pages (+ notes), isn't necessarily a casual read. But I found it consistently interesting, to the point that I insisted, over Sarah's pretty strenuous objections, on reading out bits of it to her. :-)

[categories]

technology, books

|

link

|

Wednesday, 10 June 2009

08:12 AM

I like the idea of e-book readers. But economically it isn't making sense to me.

[categories]

technology, books

[tags]

Kindle

|

link

|

Sunday, 7 June 2009

11:20 AM

Recently I finished The Invention of Air by Steven Johnson, which is a book about the English scientist Joseph Priestley, who is  best known as the discoverer of oxygen. Johnson shows how Priestley had a strong influence on both science and politics (he was a close friend Jefferson and Franklin). But Priestley also sat at a historical confluence that was conducive to, basically, Enlightenment thinking, and Johnson ties together many threads in a way reminiscent of James Burke: coffeehouses and efficient postal delivery, which fostered open and fast communication; innovations in scientific technology, which let Priestley engage in the experiments he did; the wealth of the industrial age, which indirectly provided Priestley with the time to do research; and so on. best known as the discoverer of oxygen. Johnson shows how Priestley had a strong influence on both science and politics (he was a close friend Jefferson and Franklin). But Priestley also sat at a historical confluence that was conducive to, basically, Enlightenment thinking, and Johnson ties together many threads in a way reminiscent of James Burke: coffeehouses and efficient postal delivery, which fostered open and fast communication; innovations in scientific technology, which let Priestley engage in the experiments he did; the wealth of the industrial age, which indirectly provided Priestley with the time to do research; and so on.

At times the chains of connections go quite far indeed -- for example, from Priestley's simple experiment with a mint plant all the way to the field of planetary ecology. A continuing theme is energy: sunlight to feed plants, coffee to feed scientific minds, oxygen to feed animals, coal to feed the industrial revoltuion, and so on. To discuss these last two, Johnson takes a side trip way back in Earth history to the Carboniferous era, where he tells the following story.

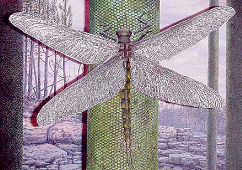

Many of the fossils that Brongniart uncovered shared a defining characteristic: compared to their modern equivalents, they were massive. He discovered ferns the size of oak trees, and flies as big as birds. In 1880 he unearthed his most startling find: a monster dragonfly (Meganeura) with a wingspan of 63 centimeters [2 feet]. Subsequent fossils have been discovered with a wingspan of more than 75 centimeters.

Meganeura was not alone. Paleontologists worldwide soon discovered that giantism was a prevailing trend between 350 and 300 million B.C., a period now called the Carboniferous era. Like some strange Brobdingnagian natural history exhibit, the landscape of the Carboniferous was populated by foot-long spiders and millipedes, and water scorpions the size of a small boy. The plant life was even more spectacular. Club mosses growing in damp forests towered above the swampland below, reaching heights of 130 feet, five hundred times taller than their modern descendants. Horsetails and rushes that now top out at around four feet regularly reached the height of a five-story building. Early conifers sprouted leaves that were more than three feet long.

The planetary fad for giantism didn’t last. The dinosaurs evolved immense body plans in the coming ages, of course, but by 250 million B.C., the rest of the biosphere had largely retreated back to the scale we now see on earth. But that pattern was distinct enough that it presented a tantalizing mystery: just as the Cambrian explosion raised the question of why life suddenly grew so diverse, the Carboniferous age raised the question of why life suddenly grew so big and how it managed to survive with such exaggerated proportions. Meganeura shouldn’t have been able to fly, given its size. The respiratory systems of modern insects and reptiles wouldn’t be able to generate enough energy to support a body plan that was ten times their current size. And yet somehow the giants of the Carboniferous managed to thrive in that exaggerated state for a hundred million years. The planetary fad for giantism didn’t last. The dinosaurs evolved immense body plans in the coming ages, of course, but by 250 million B.C., the rest of the biosphere had largely retreated back to the scale we now see on earth. But that pattern was distinct enough that it presented a tantalizing mystery: just as the Cambrian explosion raised the question of why life suddenly grew so diverse, the Carboniferous age raised the question of why life suddenly grew so big and how it managed to survive with such exaggerated proportions. Meganeura shouldn’t have been able to fly, given its size. The respiratory systems of modern insects and reptiles wouldn’t be able to generate enough energy to support a body plan that was ten times their current size. And yet somehow the giants of the Carboniferous managed to thrive in that exaggerated state for a hundred million years.

[...]

The "natural" level of oxygen on Earth was less than 1 percent; the 20.7 percent levels we enjoy as respiring mammals was an artificial state, engineered by the evolutionary breakthrough that began with cyanobacteria billions of years ago. [i.e., photosynthesis] The scarcity of oxygen before the evolution of plant life suggested one follow-up question: why had oxygen levels stabilized at around 20 percent for so many millions of years? Were it to drop to 10 percent, most of aerobic life would suffocate; were it to double, the combustion reactions of oxygen would engulf the planet in a worldwide inferno. So what mechanism allowed the atmosphere to regulate itself with such precision?

[Robert Berner and Donald Canfield researched atmospheric oxygen levels going back 600 million years.]

[Their data showed that] oxygen levels had been relatively stable for the last 200 million years. But the most startling finding came before that long equilibrium. The data showed a dramatic spike in oxygen levels, reaching as high as 35 percent around 300 million B.C., followed by a plunge to the borderline asphyxia of 15 percent in the Triassic era, 100 million years later. The oxygen pulse overlapped exactly with Meganeura and other giants of the Carboniferous.

Since then, dozens of paper have explored the connection between increased oxygen content and giantism, and the growing consensus is that higher oxygen concentration would support larger body plans in reptiles and insects. And the increase in atmospheric pressure that accompanies 35 percent oxygen levels would even alter the aerodynamics enough to allow Meganeura to take flight.

Where did all that oxygen come from? From plants, of course. First, the plants invented the photosynthetic engine that created an oxygen-rich atmosphere billions of years ago. But at some point near the end of the Devonian age, the plants evolved the ability to generate a sturdy molecule called lignin that gave them newfound structural support, allowing them to grow to sizes never seen before on Earth. Larger plants alone might have led to an oxygen increase, but lignin may also have had a more indirect role in the spike. One popular but unproven theory argues that lignin confounded the microbial recyclers responsible for the decomposition of organic matters. Plants absorb carbon dioxide and produce oxygen through photosynthesis; decomposition plays that tape backward, as bacteria and other animals use up oxygen in breaking down the plant debris, releasing carbon dioxide in the process. Lignin may have disrupted that cycle, because the recyclers had not yet evolved the capacity to break down the molecule, creating what the paleoclimatologist David Beerling calls an episode of "global indigestion." With the decomposers handicapped by lignin’s novelty, immense stockpiles of undecomposed biomass filled the swamplands and the forest floor, and the oxygen levels climbed even higher. Oxygen would not return to the 21 percent plateau until the microbes cracked the lignin code, millions of years later.

But the debris accumulated during the age of Meganeura did not disappear from the geologic record. It simply went underground. When it ultimately resurfaced, it would transform human history every bit as dramatically as it transformed natural history the first time around.

Update 2 Nov 2010: Interesting post on the Wired blog about how some biologists raised larger-than-normal dragonflies by keeping them in an oxygen-rich environement.

[categories]

readings, history, books

|

link

|

Thursday, 12 February 2009

12:35 PM

Birthday boys today, as noted practically everywhere, are Darwin and Lincoln. If you've got some spare time today, read Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address ("With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in ...").

Bible Illuminated. The New Testament meets National Geographic. Interesting idea. [via Jeff Atwood, who referred to it as "Bible 2.0"]

The Wired.Com Tech Layoff Tracker.[1] Watch the job market in the tech industry tank, bleah. Links included to other, similar (similarly depressing) tracking sites. Speaking of things economic ...

You Try to Live on 500K in This Town. The Fashion & Style section in the New York Times explains the hardship of a $500K cap on executive salaries. I imagine that the sympathy level for this situation is floating at around 0 percent. Golly, they'd have to pull their kids out of private school. Of course, many people can just kiss off higher education for their kids altogether, can't they? As but one thought.

Darwin The Dog Lover. The writer claims that Darwin's scientific skills (implication: leading to the theory of evolution) were sharpened by his interaction with dogs. Sure, what the heck, I'll buy that.

[categories]

roundup, books, general

[tags]

bible, tech industry, salaries, dogs, Darwin

|

link

|

Monday, 1 December 2008

05:01 PM

I just made the interesting discovery that within the borders of the city that I nominally live in (just outside), there is exactly one bookstore, whose primary businesss is actually "metaphysical supplies." Dang. And I don't think that there has been a collapse of a once-lively bookmongers' trade in the city, either. I think there have just never been any ever.

Not that it's impossible to find a bookstore, assuming you like mall-based and/or chain bookstores; you just gotta go over one city to Shopping, WA. (Names have been changed, but only in letter, not spirit.)

I suppose the economics of bricks-and-mortar(-and-books) bookstores requires a certain minimum population density in the store's, whatsit, catchment area. Our city, aside from a couple of huge manufacturing facilities (e.g., Boeing) is pretty much just cul-de-sacs, drug stores, and pizza places.

Still, it seems that it's representative of ... something, dunno, that there isn't a proper bookstore anywhere in the city. Possibly it's just representative of me needing to not ruminate on this too much.

PS I guess I should note that we're about a mile from a branch of the King County Library, which has served us extremely well. Not so handy for the Christmas gifts, tho.

[categories]

general, books

[tags]

bookstores, malls

|

link

|

Monday, 17 November 2008

09:23 AM

Sarah and I read a lot, and we typically have multiple books scattered around the house that are at various stages of completion. In spite of our book diet, we still are always on the lookout for new things. For example, no Costco trip is complete without a scan through the books. Instead of buying, tho, we usually write down interesting-looking titles and then add those books to our respective queues at the library.

For all the reading we do, we don't overlap that much. I read about history and technology, and I seem to end up reading novels about middle-aged men (#, #, #). Sarah reads about medicine, public health, and biography, and she'll have a go at all sorts of things might grab her eye on the shelf at the library. Plus she reads novels of all sorts, including, for purposes of parental oversight and solidarity, books currently popular with her girls (#).

The other day I found two books at Costco that seemed interesting: The Airplane by Jack Spenser[1], and Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe by Mark Mazower. I believe I've established that I have an interest in aviation. Jack Spenser was the co-author of 747: Creating the First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation, and has, among other things, been the director of the Museum of Flight here in Seattle. The book on Hitler's empire brings together an early and intense interest on WWII with the fact that I studied German in college and that one of the best classes I had was a 400-level class in 20th-century Germany.[2]

I came home and put both of these in the library queue. The library site helpfully told me that I was, respectively, #4 of 4 holds on zero copies, and #16 of 16 holds on zero copies. The library, it seems, was still waiting for their own copies, with patrons ready to read as soon as the books came in. I came home and put both of these in the library queue. The library site helpfully told me that I was, respectively, #4 of 4 holds on zero copies, and #16 of 16 holds on zero copies. The library, it seems, was still waiting for their own copies, with patrons ready to read as soon as the books came in.

Later that day I was telling Sarah about this zero-copies thing at the library. She looked at me for a second and then said, "You know ...," which I thought was a preface to a remark about the library queue. She continued, "... both of those titles sound about as interesting to me as watching paint dry." Heh. I have no idea what she's talking about. How could someone not find books about aviation and WWII fascinating, really? :-)

[categories]

personal, books

[tags]

aviation, books, history, world war II, library

|

link

|

Friday, 3 October 2008

01:39 PM

Editing Readme files today. By definition, a lot of weird technical stuff coming from all directions at the last minute. I love my job. :-)

Organizing Our Marvellous Neighbours: How to Feel Good About Canadian English. "This is a book that will give you confidence to write Canadian English well and correctly." [via Michael B]

YouTube Comment Snob. "YouTube Comment Snob is a Firefox extension that filters out undesirable comments from YouTube comment threads" based on criteria like ... more than # number of spelling mistakes, all caps, no caps, and excessive punctuation (!!!! ????). Even if this isn't for real (haven't tried it), the idea of it alone makes me happy. [via Language Log]

Sony Targets College Students With New E-Book Reader. "... includes new features like a touchscreen, note taking and highlighting with a stylus, and a front-lit screen." Alas, they're apparently targeting students who have generous student loans. Or generous parents. Dang, I so want this technology to become affordable.

How to judge a book by its cover. A video review by John McIntyre. "When a book poses a question on the jacket, ask yourself whether you really care about the answer."

[categories]

roundup, language, technology, books

|

link

|