Wednesday, 4 September 2024

08:04 AM

This week I start an Old English class in which we begin our reading of Beowulf. I believe that the arc for most (all?) Old English courses is to start with the basics, work one's way through shorter pieces, and culminate with reading the big B.

This week's assignment is to read the first 79 lines, in which Hrothgar has the great hall Heorot built. (Soon, as many of us know, it will be visited by Grendel ...) This week's assignment is to read the first 79 lines, in which Hrothgar has the great hall Heorot built. (Soon, as many of us know, it will be visited by Grendel ...)

I had to think for a bit about whether I even wanted to take this Beowulf class. Back in 1980, I took the Old English series at the University of Washington. That consisted of two parts: part 1 was grammar and shorter readings, part 2 was Beowulf, one semester (quarter?) each. As I've been taking OE classes again over the last couple of years, I marvel at how rapidly we must have worked our way through the readings. I absolutely could not keep that pace up now in my dotage.

The experience back in the day also must have traumatized me a little, because ever since I restarted Old English classes, I've been stressed about the prospect of revisiting Beowulf. I expressed this hesitancy to our instructor, who has assured us multiple times that the readings we've done so far — including "The Battle of Maldon", "The Wanderer", "The Seafarer", and the horrible (to me) "Andreas" poem — have prepared us well for tackling Beowulf.

But I also had to stop and think about a question that several people have asked me: why am I taking Old English classes at all? The answer at first was easy — because it's fun! I've had enough German to recognize and be delighted by the resemblance between OE and German, not to mention the joy of finding ancestral and fossil words of modern English.[1]

The text for our first year of OE was written by our instructor: a book about Osweald the Bear, a talking bear who has adventures in Anglo-Saxon England at a particularly interesting time in history. The text starts simple and becomes increasingly sophisticated, at times including snippets of "real" OE literature. It was a blast to read and discuss, with all of us keenly invested in what happens to Osweald and his friends. The text for our first year of OE was written by our instructor: a book about Osweald the Bear, a talking bear who has adventures in Anglo-Saxon England at a particularly interesting time in history. The text starts simple and becomes increasingly sophisticated, at times including snippets of "real" OE literature. It was a blast to read and discuss, with all of us keenly invested in what happens to Osweald and his friends.

After that we turned to existing literature, including bits from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, gospel translations, and various poems. These were more challenging, of course. That's especially true for the poems, which are syntactically complex — the subject of a sentence might be several lines after the verb and object(s), for example.

Plus poems rely on a broad vocabulary. As I heard somewhere, the alliteration used in Old English poems means poets needed a selection of synonyms that all started with different sounds. Thus, for example, the poem about the battle of Maldon has about two dozen words for "warrior", basically.[2] Until one has mastered all of this vocab (not so far, me), it can be a bit of a slog to stop and look up yet another unfamiliar word.

As the readings got harder and it took longer to get through them, I had to ask myself again whether I was having fun — or enough fun to continue. Did I actually want to read Beowulf?

I know from talking to some of the other students that many of them came to Old English through Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings. There are discussions sometimes in class about how Tolkien borrowed elements of Old English literature for his works. But I'm not a Tolkien guy (never read any of the books), so I do not get the pleasure of appreciating how the literature we're reading in class was echoed in LOTR.[3] I know from talking to some of the other students that many of them came to Old English through Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings. There are discussions sometimes in class about how Tolkien borrowed elements of Old English literature for his works. But I'm not a Tolkien guy (never read any of the books), so I do not get the pleasure of appreciating how the literature we're reading in class was echoed in LOTR.[3]

The joy of discovering correspondences and fossil vocabulary has faded a bit as I've gotten more used to Old English. I do still find pleasing word bits, though, like this from "The Wanderer":

Gemon hē selesecgas ond sincþege,

hū hine on geoguðe his goldwine

wenede tō wiste.

He remembered the hall warriors and treasure-receiving

How in his youth his gold-friend [lord]

Accustomed him to feasting.

... and learning that wenian ("accustom") is the source of our verb to wean [from].

But an unanticipated joy (unanticipated by me, that is) is that I have come to like some of the poetry a great deal. I've discovered a fondness for the fatalistic Saxon outlook on life, as well as for their pithy and wry observations. For example, the narrator of "The Wanderer", a poem in the persona of someone treading the paths of exile, makes this relatable observation:

… ne mæg weorþan wīs wer, ǣr hē āge

wintra dǣl in woruldrīce.

A man cannot become wise before he's had a share of winters in this world.

And there's this ubi sunt lamentation from later in the poem:

Hwǣr cwōm mearg? Hwǣr cwōm mago? Hwǣr cwōm māþþumgyfa?

Hwǣr cwōm symbla gesetu? Hwǣr sindon seledrēamas?

What's become of the horse?

What's become of the young warrior?

What's become of the treasure-giver?

What's become of the seats at the feast?

Where are the hall-joys?[4]

I was surprised at how much I enjoyed "The Battle of Maldon", a poem about how a troop of Saxon militia lost a battle against marauding Vikings, apparently recording a real incident. The poem is practically cinematic; you could make a movie of it today and it would hit all the tropes we're used to — the old commander rallying his inexperienced troops; the young man who sends away his beloved hunting falcon and turns to join the ranks; the ravens circling in anticipation; the old warrior who gets wounded but kills his attacker; the cowardly brothers who turn and run; the sad ends of individual courageous fighters.

And now I've started Beowulf again. The poem begins with a history of Scyld Scefing, a foundling who …

... sceaþena þrēatum,

monegum mǣgþum, meodosetla oftēah,

egsode eorlas …

oð þæt him ǣghwylc þāra ymbsittendra

ofer hronrāde hȳran scolde

gomban gyldan

... from troops of enemies,

from many nations, captured their mead-benches,

(and) terrified rulers …

until him each of the surrounding nations

over the seas [whale-road] had to obey

(and) to yield tribute

To which the poet adds this conclusion:

þæt wæs gōd cyning

That was a good king!

You can imagine a hall full of Saxons having a good whoop about that.

I don't know if I'll make it through all 3182 lines of the poem, but it seems like it has a promising start.

__________

[categories]

personal, language, readings

|

link

|

Friday, 31 May 2024

12:04 PM

The surest way to cast a critical eye on the amount of stuff that you have is to prepare for moving. The prospect of boxing up all that stuff and hauling it and finding a place to put it at the new domicile can lead a person to wonder why they even need all that. This is particularly true when you're downsizing from, say, a four-bedroom house with a double garage to, say, a two-bedroom condo with a single outdoor parking space.

We did this some years ago, which resulted in a huge yard sale and a sometimes-painful culling of all our stuff, especially books. But we did it, and in our little place we're a wee bit tight, but we manage.[1]

Chapter 2. Over this last winter, we spent about six months in San Francisco for my wife's work. During that time we lived in rentals. When we drove down, we took what we needed in one large suitcase and two small ones.[2] We bore in mind the sensible travel advice that you don't have to bring everything with you — your destination has drugstores and clothing stores (and for me, hardware stores, ha).[3] So while we were in SF, we made trips to Target and Daiso and other locales where we could fill in any missing stuff.

This worked well. Our rentals had laundry facilities, of course, so I was able to cycle through my limited wardrobe. And we were indeed able to get the additional things we needed — my wife needed some work clothes, for example. This worked well. Our rentals had laundry facilities, of course, so I was able to cycle through my limited wardrobe. And we were indeed able to get the additional things we needed — my wife needed some work clothes, for example.

But we bore in mind that these acquisitions were either temporary (to be left behind at the rentals or donated) or we'd have to haul them back with us. This mentality helped frame the question of whether to buy stuff: for everything that we acquired, what were we going to do with it when our stay in SF ended?

(One place where this kind of failed was with books — between visiting a gajillion bookstores and going to weekly library book sales, we acquired more books than we probably should have. I ended up shipping books back home via the mail before we left.)

Chapter 3. Back in Seattle! After unpacking the suitcases, I went to put away the wardrobe that had served me well during our extended leave. But when I opened my dresser drawers, I was kind of shocked: I have so much stuff. I had been living with a collection of, like, 9 or 10 shirts. But at home I have two full drawers full of neatly folded t-shirts. Why? Why would I need a month's worth of t-shirts? I had the same experience in my closet — why do I need all these shirts/pants/sweatshirts/coats?

Well, I don't.

So another culling has begun. These days, when I pull out a shirt, I might look at it, and say yeah, no, you go in the Goodwill pile. This process is not as concentrated as if we were moving again, but it's steady and I'm determined to keep at it until I'm down to a collection of clothing that I actually use. Ditto kitchen stuff, linens, office supplies, leftover project hardware, and all the other stuff that just accumulates. (Books, mmm, that one's hard.)

Taking a break from our stuff, and living adequately with less of it, has really helped us look at it again with a bit of a critical eye. I suppose "Do I really need this?" isn't exactly a question about "sparking joy", but I hope it will be just as effective.

__________

[categories]

personal, general, travel

|

link

|

Thursday, 30 November 2023

10:34 PM

Recently I was at a grocery store in our neighborhood that still does a lot of business in cash. As I was waiting, I watched the cashier ring up the customer in front of me. The cashier deftly took the customer’s bill—a $50, I think—and counted out change. When it was my turn, I said “It looks like you’ve been doing this for a while”. “Oh, yes”, she said. “35 years”.

During my college years (1970s), I had a kind of gap year during which I worked for Sears, the once-huge department store. I was hired as a cashier, and the company put us through an extensive training program for the position.

For example, that’s where I learned something that I saw the grocery-store cashier do: when you accept a big bill from a customer, you don’t just stuff it into the tray. You lay it across the tray while you make change. That way, if you make change for a fifty but the customer says, “I gave you a hundred”, you can point at the bill and show that that’s what they’d given you.

Before my timeMy cashiering days were at the beginning of the era of computerized cash registers (no big old NCR ka-ching machine for us). Although our register could calculate change, they still taught us how to count out change manually. (One method is to count up from the purchase price to the amount the customer gave you, as you can see in a video.)

We also learned to handle checks, which included phoning to get an approval code for checks over a certain amount. We learned to test American Express travelers checks to see if they were authentic. We learned to handle credit cards, which we processed using a manual imprinting machine that produced a carbon copy of the transaction.

We also learned to be on guard for various scams, such as the quick-change scams that try to confuse the cashier, as you can see in action in the movie Paper Moon.

There was of course lots more—cashing out the register, doing the weekly “hit report” of mis-entered product codes or prices (this was also before UPC scanners), and many other skills associated with being at the point of sale and handling money.

During my son’s college years (late 2000-oughts), he also worked as a cashier, in his case for Target and for Safeway. I quizzed him about his training. He remembered that the loss-prevention people at Target warned them about the quick-change scam, and it even happened to him once while he worked at Safeway.

But he doesn’t remember much training about how to handle change; at a lot of places, coin change is automatically dispensed by machine into a little cup. He does remember learning how to handle checks. But he doesn’t remember much training about how to handle change; at a lot of places, coin change is automatically dispensed by machine into a little cup. He does remember learning how to handle checks.

Most of their training, he remembers, was about how to use the POS terminal[1]—how to log in, how to enter or back out transactions, etc. A POS terminal is, after all, a computer—they were being trained in how to manipulate the computer, and less so than in my day about how to handle cash money.

Shortly after I had my grocery-store experience with the experienced cashier, I was in line at a local coffee shop. The customer ahead of me paid in cash. When I got to the counter, I asked the amenable counter person, “This is going to be a sort of weird question, but how much training did they give you in how to handle cash?” “Little to none”, was her report.

And Friend Alan recounted this experience recently on Facebook about a cashier trying to figure out how to even take cash:

It might seem like old-school cashiering skills are becoming anachronistic. It’s not unusual in my experience that small shops and pop-up vendors only take cards, using something like Square. Frankly, I was surprised that the coffee shop with the informative counter person even took cash. It might seem like old-school cashiering skills are becoming anachronistic. It’s not unusual in my experience that small shops and pop-up vendors only take cards, using something like Square. Frankly, I was surprised that the coffee shop with the informative counter person even took cash.

Moreover, we customers are more and more becoming our own cashiers. Many stores nudge customers toward self-checkout kiosks, in part by reducing the number of cashiers so that it’s faster to use the self-checkout.[2] The logical conclusion to this effort is the cashierless store (aka “Just walk out store”), where computers just sense your purchases and charge you.

Still, it’s not like cash is going to go away. Even in the age of debit cards and Venmo, people will still want to use cash for various private transactions.[3] Moreover, not everyone has a bank account, or wants one. Although individual merchants might decide to go card-only, many will still find it to their benefit to take cash.

That probably will continue to include the grocery store where I met the experienced cashier. For the sake of that store, I hope that she is able to pass her experience and training on to other cashiers who work there.

__________

[categories]

personal, general, technology

|

link

|

Friday, 17 November 2023

11:49 AM

We’re staying in San Francisco for a few months, so we’re in a rental. It’s nice enough, but there are little things here and there that feel like they could be improved. (For example, no rental I’ve ever been in has had enough lighting.) One such thing in this rental is the kitchen faucet:

I hand-wash dishes, so I like to have a sprayer attachment for the kitchen faucet. I reckoned that hey, they’re not expensive, I’ll just get one and attach it myself. I hand-wash dishes, so I like to have a sprayer attachment for the kitchen faucet. I reckoned that hey, they’re not expensive, I’ll just get one and attach it myself.

Well, not quite. I took the aerator off the existing faucet and went to a plumbing supply place, where I explained my quest to the woman. She got out one of those gauges that they use to determine size and thread count, but to her surprise, mine didn’t fit any of them.

Hmm. We went to find another guy who tried the same thing. At that point I mentioned that it’s possible that this faucet is from IKEA. Ah. “My condolences,” he said, adding that he couldn’t help me with metric sizes and threading.[1]

Being an old guy, I remembered that when I was a kid, we used to have a little shower-head-looking attachment for our kitchen sink. It just slipped over the end of the faucet. Did he have any of those? He did know what I was talking about but told me that those were long gone.

Well, not quite. I went online, and dang, there was the very thing I’d remembered:

Not only was the device still available, the web even told me that it was in stock at a hardware store within walking distance.[2] Price: $4.99.

And so I went to Cole Hardware off Market Street. The outside looked unpromising, but they’d somehow crammed a complete, old-school hardware store into a space that’s the size of a bodega—two floors’ worth.

I wandered up and down the tightly-packed aisles till I found the plumbing stuff. I had to get down on the floor and root around in the back, but sure enough, there it was: the Slip-On Wide Sprayrator (“For mobile home kitchen sinks,” wut). To my professional amusement, the instructions for installing it are wrong—they show you how to screw it on, whereas the entire point is that you don’t:

Whatever. I had to enlarge the hole a little bit, but it did in fact slip on, and I now can enjoy the benefits of a sprayer while I wash the dishes:

I enjoyed the entire experience so much—success in finding a nearly ancient piece of plumbing technology, plus my visit to Cole Hardware—that I got myself a hat that features a skyline made of tools:

At this point, it would probably be wise of me not to study our rental apartment too closely. As much as I’m now feeling empowered, I should probably rein in any further urges to improve the place.

[categories]

personal, house, travel

|

link

|

Tuesday, 14 November 2023

02:12 PM

After I published my book, I was chatting with fellow word enthusiast Tim Stewart, who was one of the first readers. At one point he noted that there are a lot of references to various religious texts, and he gently asked “Do you have a background in Christianity?”

It was a keen observation. Per a casual count, I mention or cite the Bible about ten times, and I have references to the Lindisfarne Gospel, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Dead Sea Scrolls. I also have a reference to the Quran.

I can see why someone might conclude that I might have studied these texts in a religious context. But no. I was raised outside of any faith. In fact, because I didn’t go to Sunday school (or equivalent) and hadn’t read any religious texts growing up, I’ve often thought that I’ve been at a disadvantage when it comes to Biblical knowledge.

I apparently recognized this early on. When I was in high school, I took a class that was named something like “The Bible as Literature.”[1] I don’t remember much about that class, other than that I did a presentation on representations of the Madonna in art—something that seems like the type of knowledge one can have without having any religious motivation. I apparently recognized this early on. When I was in high school, I took a class that was named something like “The Bible as Literature.”[1] I don’t remember much about that class, other than that I did a presentation on representations of the Madonna in art—something that seems like the type of knowledge one can have without having any religious motivation.

Such Biblical learning as I have came about more indirectly, when I got to university and started studying old languages. Literacy, hence written materials, for old languages often coincided with the Christianization of the people who spoke (wrote) those languages. A particularly salient case (one that I wrote about elsewhere) is that of the Gothic language: effectively, the only real text in that defunct language consists of fragments of a Bible translation.

In fact, it was a class in Gothic that sort of kickstarted my Bible-reading. Most old-language classes consist of studying grammar and then reading texts. Exams in those classes then usually consist of being given a passage and having to translate it. In fact, it was a class in Gothic that sort of kickstarted my Bible-reading. Most old-language classes consist of studying grammar and then reading texts. Exams in those classes then usually consist of being given a passage and having to translate it.

I remember our first midterm exam in Gothic. The prof handed out the text to translate, and someone in class muttered (or perhaps even shouted) "The Parable of the Talents!" It clearly was helpful to that student to know the outlines of the text already. But because I was so ill-read in the Bible, this clue did me no good at all.

This was decades before the internet, so we had to look everything up in books. Consequently, the next day I went to the university bookstore and got myself a pocket edition of the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, which I carried around in my backpack for the next couple of years.

There are of course many translations of the Bible into English, but the KJV was useful to me for two reasons. One was simply that I had a new(-ish) English version of things like the Parable of the Talents in English. But it was also useful because its antique-ier grammar often reflected more closely the grammar of the dead-language texts that we were reading.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I’m taking a class in Old English right now, and it has again been helpful to have some knowledge of the Bible. Although there is a pretty good corpus of Anglo-Saxon writing, there’s still a lot of Biblical themes. In fact, in our class I’ve already run across my old friend the Parable of the Talents, and I’ve also encountered the Old English versions of the Parable of the Ten Virgins and the Parable of the Weeds, along with a couple of other glancing references to the New Testament. In each case, I’ve found the relevant passage in the KJV (online these days) to help me decode what I’m reading.[2]

![Medieval-looking painting of the 10 virgins from the parable. In Old English: 'Syllaþ us of eowrum ele; for þam ure leohtfatu sind acwencte.' [KJV: Give us of your oil; for our lamps are gone out.]](https://www.mikepope.com/blog/images/BibleStudiesTenVirgins.png) But the content and the language of the KJV has proved helpful not just when I want to study old languages. At one point in my education, I remember hearing that it’s not possible to read Milton without having a substantive knowledge of the Bible. I don’t particularly yearn to read Milton, but it’s true that stories from the Bible infuse our literature. So my instinct in high school to take a class in Bible as literature was a good one.

And there’s more. To borrow an idea, see if you know the source of these well-known phrases:

He gave up the ghost

There is no new thing under the sun

A man after his own heart

Don’t cast your pearls before swine

The writing on the wall

Many are called, but few are chosen

Since I’ve loaded the dice here, you won’t be surprised to learn that these are all from the Bible, specifically from the KJV.

The writer Cullen Murphy performed an exercise once in which he took these phrases and several more and sent associates out into the streets to ask people where the phrases were from. People knew the phrases, but they frequently didn’t know the source, although he got a lot of amusingly incorrect guesses.

The language of the KJV has resonated with English speakers for centuries, obviously, as evidenced by how much of it we’ve incorporated into our daily speech. Dozens (hundreds?) of phrases we use all the time were crafted by “certain learned men”[3] in the creation of what in 1611 was known as the Authorized Version.

Tim Stewart, my correspondent in this discussion about the Bible, put it all this way:

On one level [the KJV] is a religious text, of course, but it's also a cultural touchstone. As random data points, in both the movies Day After Tomorrow (2004) and V for Vendetta (2005), there are nonreligious characters who have short scenes where they appreciate and nearly reverence the King James as a piece of literature and an artifact of human civilization. The King James Bible continues to attract interest and spark joy not merely for its religious content but for its enduring textual and linguistic beauty, not even to mention the way its phrases and its phraseology have insinuated themselves into 400 years of English-language literature.

As I say, Tim’s question about my faith was not an unreasonable one—as I glance through my book, it does at times seem to be a bit heavy on the citations from religious sources. But the answer really is that my dabbling in old languages has inevitably familiarized me with various religiously themed texts.

And more generally, of course, I'm an English speaker. So I’m heir to the richness that the KJV and the Bible in general has contributed to our language and culture.

__________

[categories]

personal, language

|

link

|

Wednesday, 4 October 2023

09:46 AM

Today is my first day of retirement. I’ve e-signed all the paperwork; there was a (virtual) going-away party; my computer no longer accepts my work login. I spent September “on vacation” with the idea that my last day would be at the beginning of October so as to extend my healthcare coverage another month.[1] And so it has come to pass.

Grad school, 1980 Grad school, 1980I spent just over 41 years in the tech industry, which was sort of accidental. I had moved to Seattle in 1979 to go to grad school at UW. At the end of my first year, one of my fellow students asked “Hey, do you need a summer job?” And so I ended up working for a company that provided litigation support: outsourced computer-based facilities for law firms. For us, this mostly consisted of reading and “coding” documents (onto paper forms) for things that the lawyers were looking for.

The woman who ran the company had an interesting approach to hiring the minions for this job: she hired only graduate students, it didn’t matter what major. Her theory was that graduate students had shown that they knew how to read carefully and critically. We read depositions, real-estate sales documents, all sorts of stuff. Most of it wasn’t that interesting, and our role was very specific, namely to look for keywords or particular numbers or other small details. As it happens, this was good training for my later career, though of course I didn’t know it then.

When my TA position ran out at UW, I went to work full time for that same company. The timing was fortunate. The IBM PC had just come out, and law firms were interested in what they could do with this new device. Our company quickly created a couple of document-management products, and I ended up doing support and training and even some programming. When my TA position ran out at UW, I went to work full time for that same company. The timing was fortunate. The IBM PC had just come out, and law firms were interested in what they could do with this new device. Our company quickly created a couple of document-management products, and I ended up doing support and training and even some programming.

From there, my career was similar to that of many others. I moved from this startup to another to another. One of the companies afforded me and the family an opportunity to spend a couple of years in the UK.

With my daughter at Stonehenge in 1990

With my daughter at Stonehenge in 1990

At some point I moved from being a kind of roving generalist into being a documentation writer. This was back when we still included printed documentation with a product and had to worry about page counts and lead time for printers and bluelines.

In 1992 I got a job with one of Paul Allen’s software companies (Asymetrix), and when that company started teetering, I moved to Microsoft.

I spent 17 years there in all. I had a brief period in Microsoft BoB, a product that was mocked out of the marketplace (but that imo had a lot of very good ideas behind it). I spent the rest of my Microsoft career in the Developer Division, working on a bunch of products that had the word “Visual” in their name: Visual Foxpro, Visual Interdev, Visual Basic, Visual Studio. I spent 17 years there in all. I had a brief period in Microsoft BoB, a product that was mocked out of the marketplace (but that imo had a lot of very good ideas behind it). I spent the rest of my Microsoft career in the Developer Division, working on a bunch of products that had the word “Visual” in their name: Visual Foxpro, Visual Interdev, Visual Basic, Visual Studio.

About halfway through my Microsoft stint, one of the editors retired, and I made a pitch to the manager of the editing team that she should bring me on as an editor. She took this chance, and so I embarked on a formal career as an editor; I alternated between writing and editing for the rest of my time.

When Microsoft had exhausted me, I followed some former colleagues to Amazon as a writer in AWS IAM, a cloud authentication/authorization technology. Unlike some people, I had a good experience at Amazon. Even so, when I was offered a chance to work as a writer at Tableau, I took that. And from there I again followed more colleagues and moved to Google, where I spent just over 6 years editing solutions and related materials, and trying to figure out how to leverage the work of about a dozen editors across a team of hundreds of writers.

Blah-blah. :)

I appreciate that there was a lot of luck in my career. I was in the right place (Seattle) at the right time (start of the PC industry). I had just enough background, namely a smattering of experiences with FORTRAN and BASIC. Opportunities came up at the right time (a summer job, a retiring editor). People repeatedly gave me chances or offered opportunities or made career-changing suggestions. My friend Robert (also a writer/editor) and I have over the years kept coming back to this theme: how just plain fortunate we've been in our careers.

Portrait by friend Robert

Portrait by friend RobertI have no regrets about my career. Way back when I was an undergraduate and taking a class in BASIC, the prof casually asked me whether I’d considered a computer science major. Oh, no, was my answer—my math debt was so vast that I would have spent years of coursework just to meet the math prerequisites. And so I pursued the humanities and am very happy to have been able to do so, and I like to think that I was able to blend what I learned in school with what I learned on the job.

The tech industry has its issues, no doubt. But for me, at least, it also offered an opportunity to work with many, many smart people who were doing interesting things at world-class companies. Above all—and this is a cliché, but it’s still true—I’m going to miss working with the people.

People ask what I’m going to do in retirement. I kind of kid when I tell people that the first thing I’m going to do is learn to not work. But there’s a grain of truth there. I have many interests, but which ones I’ll really get into, and whether there are other, new interests that I’ll develop, remains to be seen.

Retired and traveling

Retired and traveling

[categories]

personal

|

link

|

Tuesday, 27 June 2023

08:16 AM

Twenty years ago today, I posted the first entry on this blog. As I’ve recounted, I wrote some blog software as an outgrowth of a book project I’d been working on. The book purported to teach people how to program websites, and a blog seemed like a good exercise to test that.

It’s hard today to remember how exciting the idea of blogs was 20 years ago. Before then I’d contributed some articles to a couple of specialized publications, and I was proud to see those in print. But dang, with blogging, you could sit at your desk and draft something, press a button, and presto, anyone in the (connected) world could read it instantly.

In the early days, there was handwringing and skepticism about blogs. “The blogosphere is the friend of information but the enemy of thought,” according to Alan Jacobs.[1] And in an editorial in the Wall Street Journal, Joseph Rago dismissed blogs as “written by fools to be read by imbeciles.”

Despite these Insightful Thoughts from pundits, somehow blogging survived. (haha) In my world—software documentation—blogs turned out to be perfect for a niche that otherwise could be filled only by conference presentations, or occasional articles, or books. Blogs became a way to get news and information out fast. They were also unfiltered, as compared with company-created documentation: authors could provide personal and opinionated information. And in blogs like The Old New Thing (about Windows) and Fabulous Adventures in Coding (about programming languages), to name only two, readers got all sorts of insights into how and why software was developed as it was.

And it was all free!

Once blogging overcame the initial doubts, people and companies were keen to learn how to do it. In the mid-oughts, I was teaching classes in Microsoft Word and in editing at the local college. The woman who ran the department called me up one day and said “I think we need a class about blogging.” So I put together a curriculum and taught that class for a couple of years. Which naturally I blogged about.

A bit ironically, in my own blog I didn’t follow some of the advice I was dispensing. My subject matter was (is) all over the place, as the Categories list on the main page suggests. I also was not very disciplined about adhering to a strict schedule, about planning my posts around specific dates or events, or about optimizing for SEO. (In my defense, I’ve never thought of my blog as a commercial project, so I wasn’t very concerned about maximizing traffic, building a corporate or personal brand, etc.)

And here it is, 20 years on. Counting this entry, I’ve made 2,648 posts. A rough count tells me that I’ve written almost 900,000 words. The pace on this blog has slowed considerably, but the process has been valuable to me in many ways:

- Blogging is writing. Putting together all those blog posts has given me lots of practice and I’m sure it’s improved my writing skills.

- It’s a resource. Countless times I’ve reached back into the blog to look something up that I wrote long ago.[2]

- It’s helped people. Perhaps the high point was when some Microsoft documentation pointed to one of my blog entries as the quasi-official story on something. Per my reckoning, the blog has gotten about 2.5 million hits, so hopefully some folks have gotten some value there.

- I "met" many people via blogging, and some of those in real life, even.

- It’s helped me in my career. I’ve used the blog to (in effect) draft things that were later turned into “real” documentation. I’ve used blog entries as writing samples when applying for jobs.

But over time, a couple of things changed. One was that Google killed Google Reader, a tool for tracking blogs, citing declining usage. This seemed to indicate that the popularity of blogs had crested, but I think that that change itself also contributed to making it harder to keep up with blogs.

The real change, of course, was social media. In particular, Twitter, which sometimes has been referred to as a “micro-blogging platform”, really took the air out of blogging. (For example, you're probably reading this because of a link on a social media site, not because you saw the post in your aggregator app.)

Although Twitter isn’t a good way to capture long-form posts, its immediacy became the default first-reaction medium for breaking news. And it was a perfect way to post from a smartphone; Twitter’s original 140-character limit was dictated by the constraints of the SMS protocol that was used with phones. Some will remember that as with blogging, early Twitter faced skepticism—“Why would I want to know what someone had for lunch?” for example—but it, too, found its footing.

But, gee, what goes around. In 2012, right about the time that Google Reader went away, the Medium website was launched. “Williams, previously co-founder of Blogger and Twitter, initially developed Medium as a means to publish writings and documents longer than Twitter's 140-character (now 280-character) maximum.” (Wikipedia) And there’s also Substack at al., platforms that let authors publish newsletters, as they call them, and push them to your email. Maybe I’m a bit cynical, but the difference between a blog entry that appears in your aggregator and a newsletter that appears in your inbox seems pretty small to me.

Although the software that originally inspired this blog (Web Matrix) is long gone, the blog persists. For about 19 years, I’ve been telling myself that I’ll rewrite the code to modernize it. We’ll see.

It’s had a good run, this blog, and I think it still has value to me and who knows, maybe to others. I’ll check in again in five years. :)

[categories]

blog, personal, writing, technology

|

link

|

Sunday, 2 April 2023

08:08 PM

A couple of weeks ago I sat down at my main home computer and was greeted with the message “No bootable device.” Uh-oh. I’ve had this old HP desktop for something like 9 years. About 5 years ago I swapped the ailing hard drive for a solid-state drive (SSD), which had been working great.

One of my colleagues pointed out ominously that SSDs tend to fail catastrophically; you don’t get a couple of days or weeks of squeaks or other alarming noises, the way you usually got when an old-style hard drive was ailing. I had some dim hopes that maybe the issue was that it was a BIOS problem, and that the issue was just that the computer had lost its memory and forgotten that there was an SSD attached via SATA.

Alas, no. I took it to a guy who confirmed that the SSD drive could not be read, not even for ready money. He also pointed out that my computer was quite old, something I already knew—Windows had given up on urging me to update to Windows 11.

New box

So, new computer. This gave me pause. Since 1987 or thereabouts, I’ve always had a desktop computer tucked under my home desk, and then later a separate laptop for mobile use.[1] But did I need that anymore? I guess not. I have only a laptop for work and have learned the wonders of using hubs to attach all the peripherals—big keyboard, external mouse, monitors, etc. Laptop as a Desktop (LaaD), haha. So I ordered a ThinkPad, a solid laptop for business, and I’m going to see if I can do everything from now on using a single mobile computer.[2]

The new computer is nice enough; I mean, it runs Windows 11. Plug-and-play works very well. I haven’t even had to think about drivers, including for my external monitors and printer. I don’t want to jinx it or anything, but so far “it just works.”

But I am of course faced with the task of reconstructing what I had on my old computer. This has been a bit daunting.

Did I lose data?

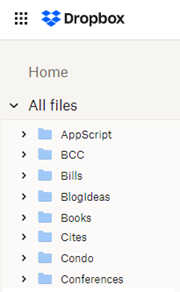

The most pressing question was what data I might have lost. On the old box, I’d managed this in a number of ways:

- A program (iDrive) that performed an ongoing backup to the cloud of the folders I told it to back up.

- Auto-synced folders (Dropbox, OneDrive, and Google Drive) whose contents were copied to the cloud.

- A scheduled script that backed up my Word templates (e.g.

Normal.dotm).

- Copies of some stuff that I had on my Yoga laptop.

My conclusion is that I think I still have most of the data. I say “think” because for sure there were some folders that were not auto-synced and not included in the iDrive backup, but of course I don’t remember (and cannot look up) what those might have been. I imagine that over the weeks and months I’ll ask myself “Didn’t I used to have a file with <thing>?” and wonder whether it was lost in the disk failure.

All those installed programs

My backup wasn’t a disk image, just data, so it couldn’t restore applications that I’d installed.[3] This meant that I was going to have to reinstall all the apps that I use. I was not looking forward to this. I also knew that I’d lost some programs that I could never recover. For example, I’ve been nursing a truly ancient edition of Photoshop Elements that I still used occasionally. Sad.

Windows 11 surprised me pleasantly by recognizing that I was on a new computer and offering to reinstall anything that I’d gotten previously through the Microsoft Store. That wasn’t a huge number of programs, but it did include Microsoft Office, so that was one less thing to worry about.

I don’t have an inventory of everything I’d ever installed on my old computer. I expect the process of reinstalling to be ongoing, and in the weeks to come I imagine myself reaching for some utility that I’ve used and remembering that oops, that’s not installed on this box.

As I said, a lot of the data I had was on synced drives like Dropbox. But to get to that data, and to mirror it back to the new computer, I needed to install password-protected apps like Dropbox. Which brought up the issue of passwords.

Bootstrapping security

To access or reinstall programs, I needed a lot of passwords. I use a password manager, so I had to bootstrap that: I had to install the password manager first so that I would have access to all the passwords I’d need for everything else. To do this, I went to the website for the password manager and signed in. Did I have the password for that? Yes. (Whew) That let me install the password manager app and the Chrome extension, which in turn helped me get logged in to many other sites that I was going to need.

I also occasionally needed product codes. I also had copies of those, thank goodness. (You probably can recover product codes from the product website, assuming you have the password, but it wasn’t an issue for me.)

On the plus side, once I’d logged in to my Google account, all my Chrome bookmarks were synced. Same with my Microsoft account and Edge and Office.

Re-logging in to all my many and various accounts meant that I got tons and tons of requests to use two-factor authentication—my Yubico key got a real workout, and I got a lot of SMS messages with one-time passwords. I also got tons of emails alerting to me to new logins from an unknown computer. This is all expected and I’m thumbs-up on 2FA and notifications, but dang, there were a lot of them. Re-logging in to all my many and various accounts meant that I got tons and tons of requests to use two-factor authentication—my Yubico key got a real workout, and I got a lot of SMS messages with one-time passwords. I also got tons of emails alerting to me to new logins from an unknown computer. This is all expected and I’m thumbs-up on 2FA and notifications, but dang, there were a lot of them.

Some lessons for me

This type of event should be a learning experience, right? Here are some things I think I’ve learned:

- Sync everything to the cloud? Should I keep all my data in auto-synced folders? I haven’t completely thought this through—like, do I want everything on the cloud?—but I’m leaning that way right now.

- Keep copies of important keys. Kee a copy of passwords and product keys somewhere “safe,” i.e. off the machine. (Maybe not in the cloud, and definitely not on sticky notes on your monitor.)

- One laptop to rule them all. It might just be possible for me to wave bye-bye to my Era of Desktops. But …

- Do I even need a laptop-laptop? As noted, the important stuff seems to have been preserved in the cloud. These days I’m constantly using cloud-based apps (Google Docs, etc.). Would it make sense for me to use a Chromebook equivalent? I thought about this, but my conclusion for now is that I’m not ready to have a computer that requires an always-on connection. And I still like the installed (as opposed to web-based) apps like Office.

One result of starting over with a clean SSD (I hesitate to call this a “benefit”) is that it could inspire me to organize my storage differently. In the past, whenever I’d gotten a new computer or a new disk, I would just copy everything over as is. This habit perpetuated a lot of cruft—duplicated files, duplicated folders, related information scattered in different places, and tons of old stuff. (Those teaching files from 2009? Maybe I can purge those.)

It hasn’t been a, you know, fun experience to be forced to get a new computer and configure it. I can say that the process has not been as bad as it could have been, had I not had synced folders and so on. I’m sure I will continue to have pangs of regret about something or other that appears to have been lost. And hopefully It’s not an experience I’ll have to revisit too terribly soon.

I was sharing all this with my friend Alan, with whom I’ve spent some quality time in the computer business. His response: “Remember when it was exciting to get a new computer?”

[categories]

personal, technology

|

link

|

Thursday, 25 August 2022

04:13 PM

I get to celebrate a handful of anniversaries today, this month, and this summer, and I thought I'd reflect on them.

Today

Back in February (my birthday month), my wife had the ingenious idea of getting me a monthly pass to our local recreation center, which has a pool. They had just tentatively reopened after Covid, and as I discovered, hardly anyone knew they were open. On February 25, I made my first trip to go swimming. This kickstarted a looong-overdue effort to exercise again.

As I've gotten older, I naturally have gotten heavier, but the pandemic era was particularly bad for me. I sat at my desk for two years, basically, and shoved food into my face the whole time. At the beginning of the year—resolution time—my wife asked what I wanted to accomplish. My answer was that I wanted to lose enough weight that I didn't gasp when I tied my shoes. Hence her idea of the swimming pass.

I started tracking my exercise and my weight in order to stay motivated. As the weather got warmer, and as the pool became more and more crowded, I switched my exercise regimen to walking. In the last 6 months, I've swum 45 miles, walked 650 miles, and climbed 13,000 stairs. I've also started playing occasional pickleball and I recently replaced my stolen bike and started riding again. I started tracking my exercise and my weight in order to stay motivated. As the weather got warmer, and as the pool became more and more crowded, I switched my exercise regimen to walking. In the last 6 months, I've swum 45 miles, walked 650 miles, and climbed 13,000 stairs. I've also started playing occasional pickleball and I recently replaced my stolen bike and started riding again.

This was part of my overall ELEM plan: eat less, exercise more. In addition to moving more, I, er, adjusted my diet. I ate less, and I substantially cut down (but didn't eliminate) sugar, rice, pasta, bread, and alcohol.

At the six-month mark, I can say that I achieved my goal. I lost 13% of my body weight and, hey, I can now tie my shoes without gasping.

This month

This month marks my five-year anniversary at Google (or Googleversary, as we say at work, since we Google-ize everything). The time sure went fast, boy howdy.

People often ask how I like working at Google. My answer is that I've enjoyed this job as well as anything I've done in decades. I really do love editing, and I get to edit engineers who are doing interesting, complex, high-impact things for customers. Back when we were still going into the office, we would get into fascinating discussions about all manner of topics, since the editing crew and the folks who sat near us had widely diverse backgrounds. (Well, the humanities is probably overrepresented on the editing team, it's true.) People often ask how I like working at Google. My answer is that I've enjoyed this job as well as anything I've done in decades. I really do love editing, and I get to edit engineers who are doing interesting, complex, high-impact things for customers. Back when we were still going into the office, we would get into fascinating discussions about all manner of topics, since the editing crew and the folks who sat near us had widely diverse backgrounds. (Well, the humanities is probably overrepresented on the editing team, it's true.)

Doing this type of work under the auspices of a large company has also been great. Unlike the situation at some (many?) companies, we're treated like adults—people who have lives outside of work that we also need to look after. I have appreciated this aspect of Google immensely.

Anyway, I don't want to blather on too much about this phase of my career, because another anniversary is …

This summer

I went into the tech world in the summer of 1982, meaning I've been at it for 40 years this year. I'd been in graduate school and had gotten a summer job working for a company that did [*waves hands*] computer stuff for law firms, using a minicomputer. When I decided to quit grad school in June of 1982, it was easy to move full time into computers.

The timing was fortuitous. The IBM PC had just come out and there was a lot of interest among professionals—like, oh, law firms—in what people could do with these things. The place where I worked got hooked up with a company that made a database product for the PC, and we put together some applications for document tracking and such-like. So I started doing work on the PC. I did training, I did support, I did a bit of coding. It was all new in those days, the demand for computer stuff far outstripped the supply of people who had formal training, so many of us learned on the job. (And pre-internet, I guess I could add.) The timing was fortuitous. The IBM PC had just come out and there was a lot of interest among professionals—like, oh, law firms—in what people could do with these things. The place where I worked got hooked up with a company that made a database product for the PC, and we put together some applications for document tracking and such-like. So I started doing work on the PC. I did training, I did support, I did a bit of coding. It was all new in those days, the demand for computer stuff far outstripped the supply of people who had formal training, so many of us learned on the job. (And pre-internet, I guess I could add.)

I was in my go-go 20s then, and for the next couple of decades I put in very long hours. That first job gave me (and the family) an opportunity to spend a couple of years in the UK. I moved around in the industry—Asymmetrix, Microsoft, Amazon, Tableau, now Google—doing mostly documentation work at different places.

Portrait by my friend Robert

Forty years is a long time to be in any type of work, and I've certainly considered retirement. My financial guy claims I could do it if I wanted. (He and I differ in how rosy our view is of the coming global economic meltdown, haha.) But I have no urgent reason to retire—I like the work, and it seems like I can now do it from almost anywhere on the globe. I still learn new things all the time, which is definitely an upside to working with such smart people. Another plus is that I experience twinges of impostor syndrome only rarely now. :) And to be honest, I worry slightly that retirement would remove me from a stimulating and rewarding environment. For now I'm playing it by ear. Check back in a bit.

Bonus anniversary!

September 1 is also the anniversary of the date on which I arrived in Seattle. I've reflected on that in the past, so I'll just link to an earlier post about that.

[categories]

personal

|

link

|

Sunday, 6 June 2021

01:23 PM

Over the last year and some, we didn't dine out, obviously, since we couldn't. Now that we're easing back into more normal life, I've realized that a year away from the lure of going out to eat has changed my thinking about it a bit.

Of course, many restaurants survived by offering take-out food. We got take-out a few times. But I realized that I didn't like this very much. For one thing, the third-party delivery services have been accused of some shady practices. But even if you order directly from the restaurant, it's a suboptimal experience. My summation of the experience of take-out food is this: cook something; leave it sitting for 20 minutes; serve and (probably don't) enjoy. Now I get take-out only if I intend to eat it more or less immediately. Of course, many restaurants survived by offering take-out food. We got take-out a few times. But I realized that I didn't like this very much. For one thing, the third-party delivery services have been accused of some shady practices. But even if you order directly from the restaurant, it's a suboptimal experience. My summation of the experience of take-out food is this: cook something; leave it sitting for 20 minutes; serve and (probably don't) enjoy. Now I get take-out only if I intend to eat it more or less immediately.

One of the first things that changed was that we cooked more at home. I'm a, dunno, utilitarian cook: I can make a certain number of things, but I don't aspire to fancy cooking. What the enforced time away from restaurants did, though, was to encourage me to work on cooking things I like. For example, I like going out for diner-type breakfast. Over the last year I actively worked on re-creating that food at home. This was a success for me: I've made waffles, hash browns, eggs over easy, French toast, and hash that to me was entirely satisfactory. (I emphasize that I can now cook these things the way that I like them, not that I should work in a diner.) There are also lunch and dinner foods that I feel that I've perfected for my individual taste. (Same caveat.)

Homemade hashbrowns and eggs Homemade hashbrowns and eggsThis success has made me ponder the purpose of going out to eat. Certainly I (you too?) have paid for pretty indifferent restaurant meals. At this point, I ask myself why I should go out for a breakfast that I can probably do better (same caveat) at home. Should I wait in line on a Sunday morning to eat a mediocre breakfast? Do I really want to go out for another meal of American Mexican food? I'm beginning to wonder.

Then there is the cost. Any sit-down meal is going to cost $18–20 per person and of course can cost many times that. If I go out for dinner with my wife, we can easily be looking at, what, $50 at even a two-$$-sign restaurant, especially if we get drinks. If one or more of the kids come along, multiply that number. It's not that these prices are unreasonable; it's that it adds up. How much per week should I budget to get meals that have a likelihood of being pretty forgettable?

But dining out is not just about meals that you might or might not be able to make at home. Going out is about third places—not home, not work, but a third place. For example, unlike my parents' generation, we don't "entertain" at home in the way that seemed to be a premise in many 1950s-era cookbooks. If we want to socialize with people, our custom (and I suspect that of many folks) is to meet up for coffee or lunch or a beer. Obviously, socializing over a table—socializing at all—was severely constrained over the last year and some.

Pages from "The Joy of Cooking" (1975) about entertaining Pages from "The Joy of Cooking" (1975) about entertainingMy wife and I also enjoyed taking our laptops to a coffee shop or pub and working or writing. (I wrote many blog posts at an ale house that was within walking distance of our last domicile.)

Did these protocols change over the pandemic time? I have started meeting people again to catch up, and it's the same as before—find a place convenient to both parties, and then have breakfast or a beer or whatever. But I am much more aware now that I'm paying to socialize, so to speak, and I'm maybe a little more resentful when I shell out a hunk of money for something that wasn't very good, the company itself of course excepted. (It's great to see people in person again.)

Based on my limited experience again of working or writing away from home, I know that I still enjoy that. Coffee shops are opening up again to allow people to sit and work; my wife and I spent a couple of pleasant hours at a coffee shop a few Sundays ago plugging away on our respective writing projects.

Back to writing at coffee shops Back to writing at coffee shopsIt would be easy to get back into a habit of going out 4 or 5 times a week to do this. But it's possible that pandemic-time habits have made me rethink all this. Although it will be easy again to think that I'm too tired to make dinner at home and go out, I've gotten out of the habit. I think about whether I'll enjoy it and how much it costs. The same is true for grabbing the laptop and settling at a table somewhere to work. Fortunately, our libraries are opening up again to allow people to sit and work: a third place that doesn't cost anything to use (though the hours are not always convenient).

I don't think we'll change our socializing habits, though; I anticipate that we'll still meet people out in the third place. But the pandemic reset expectations about socializing, I think. We went months without seeing anyone in person, and I'm still okay with limiting face-to-face socializing to just occasionally, maybe a couple of times a month at most. In this regard I think I differ from my wife, who is not as content as I am to have long periods between visits.

I've read a number of articles about how there's pent-up demand for things to get back to how it was in pre-pandemic times. I suspect, though, that for some of us, the forced changes over the last year have done a reset on our expectations and, possibly, on our habits.

[categories]

personal, general

|

link

|